The Problem of “Problematic” Literature

By reading and discussing a literary work from a different era, one can see how people in that time thought, acted, loved, and hated. The contemporary reader, though, may find attitudes and language from these periods offensive or derogatory.

I’ve recently talked to several students and teachers at Boulder High who are perplexed by the question of how to approach in-class works of literature that contain what would now be considered “problematic” attitudes and language concerning race, religion, or sexual identity. I too have thought about this issue, especially in our current polarized social climate, where political correctness is pervasive and unavoidably filters into the classroom.

It isn’t a suitable solution to simply erase classic works such as Huckleberry Finn or Invisible Man— where the “n-word” is used repeatedly—from the curriculum to avoid having to confront the racist moral standards and uncomfortable interactions they include.

But if, as a school and a society, we choose to continue to use these works in class, what ground rules need to be set to guarantee that the books can live up to their full educational potential while still respecting and acknowledging the power and oppression embedded in their ideas and words?

This is a difficult question to answer, but what is clear is that we need to discuss how social relations and ethics change over time before we can begin studying such literature. Here’s why.

A discussion of this nature allows students to have a say in their own education. I think a lot of students feel more inclined to participate in a class if they feel that teachers take into account and value their opinions. By starting out a study of a book by relating it to today and their own lives, students can feel more connected to what they’re reading, enriching the educational process as a whole.

A frank conversation also helps clarify what words (i.e. racial, religious, classist, homophobic slurs) are acceptable to use when reading aloud or quoting a work, which are not, and why. Talking about how social relations have changed over time is an excellent opportunity to discuss the oppressive roots and weight of certain words, and why as a society, we have now decided not to use them in most contexts. At Boulder High, a majority white school, it is especially important to acknowledge how these words affect those they target. Through this conversation, the students and the instructor can then decide how to approach the reading of these words out loud in an educational setting.

Literature teaches us as much about history as it does about writing and language. I really like how Brian Morton voiced this concept in his essay for the New York Times in January, writing that “we’d all be better readers if we realized that it isn’t the writer who’s the time traveler. It’s the reader. When we pick up an old novel, we’re not bringing the novelist into our world and deciding whether he or she is enlightened enough to belong here; we’re journeying into the novelist’s world and taking a look around.”

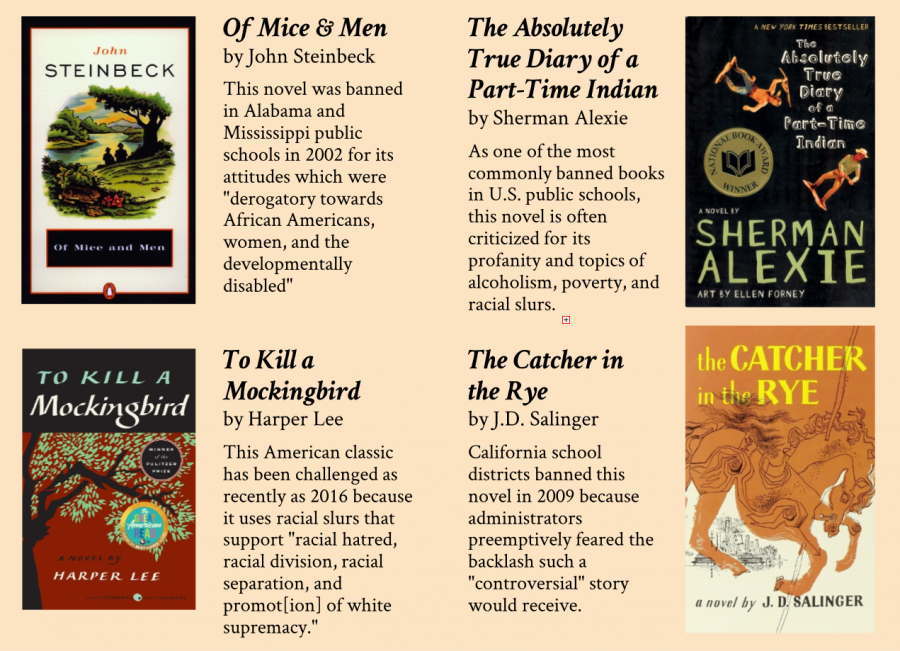

Some object to the notion that students should discuss potentially offensive language and ideas embedded in works of literature in class and that authority figures, such as parents and teachers, should simply make decisions about how to teach this content to students. Around the country and even in BVSD, due to the input of parents, certain books have been cut from the curriculum because of their “difficult” themes. But isn’t this exclusion as problematic as the books’ ideas supposedly are?

In certain cases, a literary text may deal with themes that are too triggering for some people to read. These situations should be dealt with on a person-by-person basis, acknowledging the validity of students’ vulnerabilities. But simply avoiding these issues across the board shelters students from the realities that exist in our world, perpetuating ignorance instead of opening minds.

Additionally, some teachers dispute the idea that certain words should not be spoken by certain people, even in the classroom, because they view it as a form of academic censorship. They are entitled to have this concern, given our present social and political climate. However, an open conversation, even if it does result in a class deciding not to use certain words, actually combats censorship. By definition censorship closes off topics and personal expression, but such a discussion realistically opens a dialogue between generations and those with different perspectives on the world.

These ideas of academic freedom, cultural relativism, and trigger warnings are difficult to discuss, much less channel into concrete change. Answers are hard to come by, but I can say that, whatever your opinion may be on these issues, it is crucial to talk about them before diving into hard-hitting literary works. We must all try to understand the context in which the literature we read was written to better understand history, our current world, and how we can all work to better the future.