The Fight to Spill Our Blood

Are Restrictions on MSM Donating Blood Warranted?

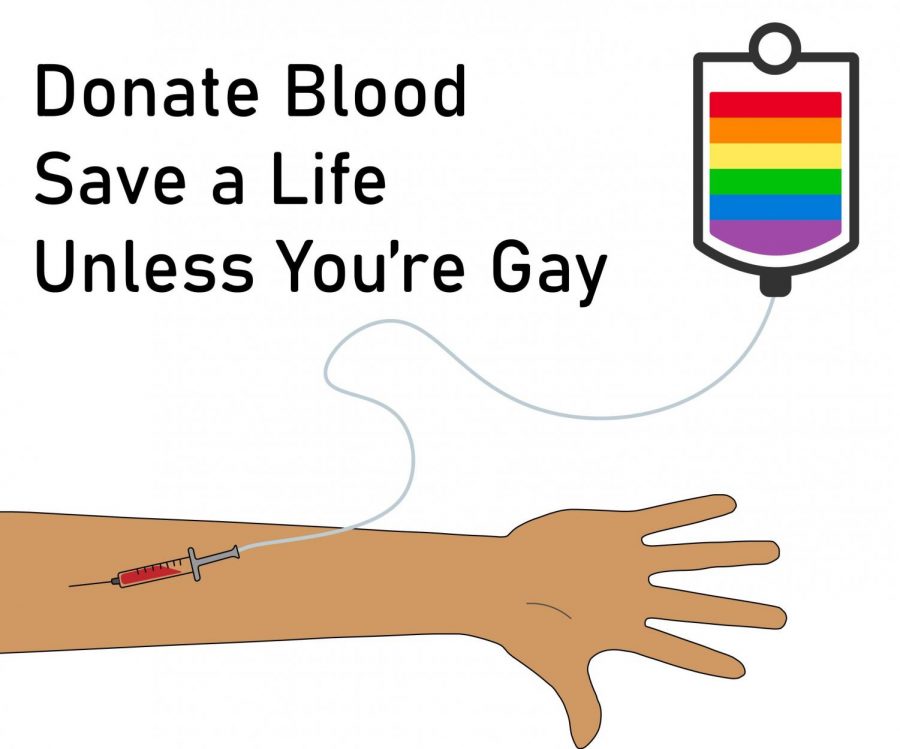

A more accurate campaign for encouraging blood donation would likely take this form.

Since 1983, Men who have Sex with Men (MSM) worldwide have been restricted from donating blood. Today, despite greater knowledge and testing technology for HIV/AIDS, these restrictive laws are still in place. Is this an instance of institutionalized homophobia or merely a sensible health measure? Regardless of where you stand, it is evident that this rule reinforces harmful stereotypes against gay men.

In the early eighties, the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) – which causes the deadly disease, Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS) – was rapidly spreading throughout the nation. The high concentration of this virus within gay communities led to a widespread belief that HIV/AIDS was a “gay disease.” At the time of the initial outbreak in 1981, little was known about how the virus spread, who could contract it or how to treat it. Until 1999, there was no effective method of testing blood for HIV itself, according to NBC News. Due to these great unknowns and the significant risk of infected blood, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) declared that gay men were a “high-risk group” when it came to blood donation, alongside sex workers and IV drug users. In 1983 the FDA also added this question to the blood drive questionnaire: “Are you a male who has had sexual contact with another male since 1977?” Answering yes to this question immediately disqualified the donor…for life.

It’s hard to be anything but understanding when looking back at the origins of this law. The early days of the AIDS epidemic were rife with fear; in the words of Dave Ensign, a longtime advocate for LGBTQ rights, “At the time there was so much concern about the transmission that I understood why such a restriction would be in place.” He goes on to explain that at the time, many people, especially hemophiliacs, were contracting HIV through blood transfusions, saying as a result of this, “There was definitely a need to take action then.” Once the lifetime ban on gay men donating blood was put in place, the number of contractions via blood transfusions dropped significantly. This proved that the rule’s implementation was a reasonable measure that undoubtedly saved lives at the time. However, due to modern testing methods and greater knowledge of how HIV spreads, this rule may no longer be pertinent.

In the early to mid-nineties, testing revealed that all people, regardless of sexual preference, were susceptible to HIV/AIDS. In 1999, Nucleic Acid Testing, or NAT, was developed. NAT allowed for batches of blood to be tested directly for HIV. This meant that blood banks could test their blood supply for contamination, which they continue to do today. In 2015, this test’s existence convinced the FDA to strike down the life ban on MSM donating blood. The ban was replaced by a rule stating that “If a male has engaged in sexual contact with another male within the past year, he may not donate blood.” This modification to the original rule was undoubtedly a step in the right direction, but studies show it still may be overkill. The reason that NAT testing has not led to the end of all sexuality-related restrictions is 1) the fact that there is a 10-25 day lag period where positive blood may text negative and 2) MSM remain 67% of the infected HIV population. It is this narrow risk window alongside the greater likelihood of MSM being HIV positive, which rationalizes the continuation of restrictions on MSM.

Opening up blood donation to MSM certainly comes with great risk (infecting blood recipients) but is this risk worth the propagation of stereotypes, and how harmful are those stereotypes? A long-standing stigma attached to gay men as a group is excessive promiscuity. The knowledge that MSM are prohibited from donating blood serves to many as an example that they are sexually reckless.

Ensign recounts a story from New York in the 1980’s saying, “I was walking through campus a nurse was standing outside the campus medical center, and she was trying to recruit people to come in and give blood. The first time I saw her, I just smiled and walked by, but the second time I saw her, I said, ‘well, I’m a member of a high-risk group,’ and she just recoiled in horror. It was quite an impactful moment that I’ll remember forever, that she had that reaction to me. It was at a time that we were trying to talk about these issues, but boy, it was hard because of the way that people would react.” This story is an example of how MSM’s association with being HIV positivity has served to ostracize and isolate MSM individuals. Even today, despite people no longer recoiling in horror at MSM, the medical world’s refusal to accept MSM blood donation continues to set the group apart. It stigmatizes them as “High Risk.”

Beyond simply ending stigma, the world has 816,000 pints of blood per annum to gain from lightening up restrictions. In times such as these, when we are facing a national blood shortage due to COVID-19, “gay blood” is needed more than ever. Despite the risk of infection, these 816,000 pints could help to save countless lives. In my opinion, the good which could be done with increased blood donations outweighs the narrow risk of infected blood supply. Since the outbreak of COVID-19, the FDA has already lowered the abstinence period to three months. It is time that they do more to save lives and end stigma.

Essentially, the question comes down to something that in a post COVID era has become greatly prominent, “How much is a life worth?” HIV/AIDS is a terrible disease; death by it can be slow and excruciating. However, now due to a modern cocktail of medications, an HIV positive individual can live a relatively normal life for years. In two cases, the virus has even been entirely cured. Is giving an individual or at worst many individuals this fate through blood transfusion so terrible a consequence? Well, that depends. For instance, for a low income individual contracting HIV, it may still be a death sentence due to the high cost of treatment and meds. However, many people who can afford the meds can live for decades with only moderate health consequences. Obviously, no one should have to live with HIV/AIDS, but if it means those in need of blood transfusions get their blood, and one of the last holdouts of institutionalized homophobia is abolished, it might just be worth it.

Blood banks do not have to do away with all restrictions at once. For instance, there are multiple ways in which blood banks could vet potential MSM donors to increase their blood supply while keeping it clean. First off, questions such as “are you in a monogamous relationship?” “When was the last time you were tested for HIV?” and “are you exhibiting any symptoms of HIV?” could root out higher-risk individuals while allowing more MSM to donate. Secondly, since HIV tests are readily available at health clinics across the nation, it would be an easy measure for blood banks to merely require a negative HIV test since the last sexual contact with another male.

In the end, there is no way to know if letting up restrictions will have significant medical fallout. What is most important is that we continue to educate people about HIV/AIDS to undo harmful associations between the disease and MSM. It is also imperative that the FDA and blood banks nationwide start considering ways to open up blood donation to MSM in the most controlled and safe ways possible. Through careful and well-measured science, we can find to make sure that every person, regardless of sexual preference, has the same opportunities to contribute to their communities’ health. Let’s not forget that the ‘H’ in HIV stands for Human, not Homosexual.

Grady is a senior and first-year staff member on the Owl. He’s looking forward to writing interesting pieces about things he cares about and sharing his ideas and opinions with his peers. When not writing an article (or trying to find something to write about), Grady is probably reading, hiking, practicing tea ceremony, or cuddling with his dog. Although Grady finds all kinds of grapes to be delicious, he has a particular fondness for cotton candy grapes. These grapes are beautiful little pops of sweetness that defy the laws of nature. They are, however, green, making Grady a fan of green grapes.